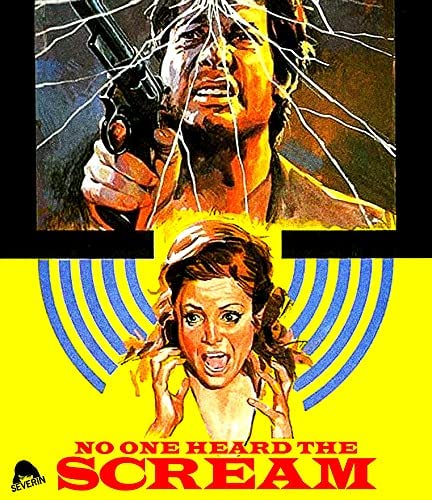

Review—No One Heard the Scream (Severin)

Author: Palo Sionoplia

Last month, Severin blessed cult film fans with the release of five Eloy de la Iglesia films (spread across three blu-ray releases). This is a boon to those of us in the USA who’ve only had access to a few of these films via subpar transfers. Severin rights this wrong and shines a much-needed spotlight on the career of one of Spain’s bonafide cinematic mavericks.

No One Heard the Scream, one of the most compelling and underseen works in de la Iglesia’s diverse filmography, is a blu-ray debut—actually, you won’t find it on DVD, either—that fans of gialli cinema (and its many offshoots) will relish. While the film features frequent nods to Argento and Hitchcock (particularly Rear Window), de la Iglesia puts his own stamp on this tale of a murder with an accidental eyewitness. No One Heard the Scream subverts giallo conventions by suggesting that the viewer has all the relevant information from the outset (though, of course, it’s a ruse). There is no black-gloved killer to be found here; instead, the killer is in plain sight. Nevertheless, there are layers of surprises, and the final twist will stupefy even the most seasoned viewer.

Although No One Heard the Scream borrows heavily from the giallo template, this is unmistakably a Spanish film, replete with brilliantly subtle criticisms of Francoist politics, theological musings, and fantastic exterior shots of 1970s Spain. Additionally, De la Iglesia also highlights male eroticism in a manner that is comparable to his most famous film, Cannibal Man. If you’re wondering how the filmmaker could get away with this material in 1973, the answer will make you smile: de la Iglesia was smarter than the censorship board. No One Heard the Scream frames highly subversive content in a way that the censors—upstanding bourgeoise from well-to-do families, no doubt—couldn’t even understand what they were seeing. Thanks to their inability to understand de la Iglesia’s filmic sophistication, No One Heard the Scream film managed to sail through a typically merciless censorship board.

Severin’s HD scan from the original negative is an unqualified success. Details are sharp and evidence of print damage is minimal. Those exterior shots are particularly pleasing to the eye, and, if your TV is large enough, you might just feel like you’ve stepped onto a Spanish beach. The audio track also fares well; dialogue is clear, and the soundtrack is vibrant and well-balanced.

While the blu-ray features a sole supplement, it’s an excellent addition. “Truth 24 Times a Second: Eloy de la Iglesia and the Spanish Giallo” (24 mins) features an informative discussion with Andy Willis, professor of film and media studies at the University of Salford. Willis contextualizes much of de la Iglesia’s career and its relationship to Francoist and post-Francoist Spain. Hopefully viewers can get past the fact that this segment is brought to us via Zoom (thanks, Covid), as it’s a wonderfully informative watch.

It is my hope that this release (and Severin’s Quinqui collection, which I’ll address in a separate review) sparks an interest in de la Iglesia’s work that extends beyond Cannibal Man, his most well-known film in the states. If ever a prolific, controversial director were deserving of rediscovery, is it de la Iglesia. an iconoclast who delivered subversive cinema during one of Europe’s most repressive political regimes. Viva la revolución!