Review—Eloy de la Iglesia’s Quinqui Collection (Severin)

Author: Palo Sionoplia

I’ve seen more cult films than you’ve had hot dinners. On demand, I can rattle off multi-page lists of gialli, yakuza films, SOV disasterpieces, Bollywood classics…you get the picture.

Two weeks ago, I couldn’t tell you a thing about the Quinqui genre.

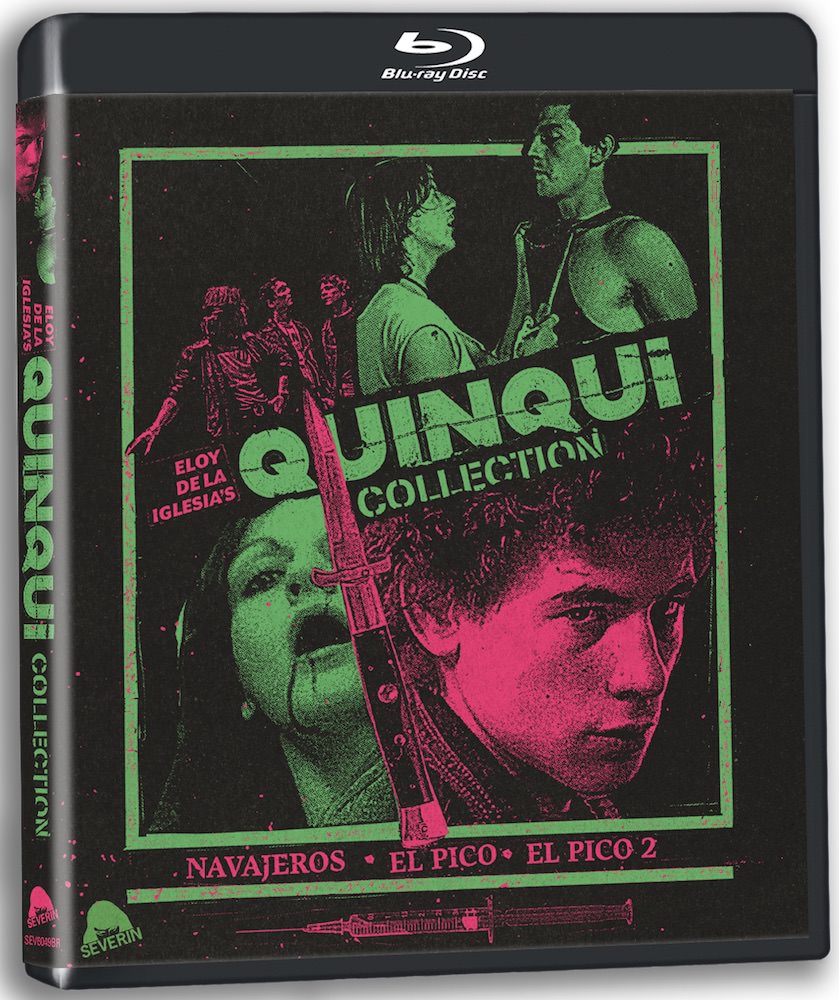

Thanks to Severin, this egregious gap in my film knowledge has been corrected. The label’s Quinqui Collection collects three of Eloy de la Iglesia’s contributions to the genre and packages them with valuable supplements that contextualize the films. The Quinqui Collection is a box set disguised as a single catalog title and belongs on the shortlist of 2021’s best releases.

In short, Quinqui cinema is Spain’s rendering of juvenile delinquent cinema, uniquely framed in the early years of the post-Francoist era. Awash with a host of new freedoms and political tension, Quinqui tracks the downward spiral of a displaced generation, the young and disenfranchised who belong neither to Franco’s totalitarian regime nor to the coming democracy. The teens and twenty-somethings who star in these films navigate a new world rife with street brawls, overt sexuality, and, most disastrously, heroin addiction. We might consider Quinqui an offshoot of Italian neorealism; like that earlier style, Quinqui places untrained actors in starring roles. Sadly, several of Quinqui’s brightest stars would end up dead or in jail, just like the characters they portrayed onscreen.

The Quinqui Collection kicks off with Navajeros (“Knivers”), the most frenetically paced and action-packed of the three films on offer. Navajeros fictionalizes the story of real-life Spanish delinquent “El Jaro,” and, like each film in this collection, stars José Luis Manzano. While there are moments in this film that play like a Spanish rendering of The Warriors, Navajeros has its own unique set of socio-political problems, played against a dizzying array of high-stakes heists, prostitution rings, and devil-may-care drug use.

The collection’s second film, El Pico, may be the most famous work in the set, and it was the most commercially successful release of de la Iglesia’s storied career. The film traces the frayed relationship between a respected police captain and his heroin-addicted son (again played by Manzano). While I can’t prove it, I’d bet my house that the many excruciating close-ups of heroin abuse are unsimulated. El Pico is de la Iglesia’s most extreme, and, at the same time, most touching contribution to the Quinqui genre, as the ever-widening rift between father and son is almost as difficult to watch as the parade of tightly-framed heroin injections.

El Pico 2, the final film in the Quinqui Collection, represents a stark tonal shift, and de la Iglesia is to be credited for not merely repeating the successful notes of the film’s predecessor. El Pico 2 is a two-hour rumination on consequences, and, as you may imagine, those consequences are grim indeed. Knowing that lead actor Manzano would come to a similarly tragic end makes this an especially painful watch. El Pico 2 is about a generation that must choose between adulthood or an untimely death, and, unfortunately, the lion’s share of its characters face the latter.

All three of these films have been scanned in HD from the original negatives, and the effort shows. Picture quality is sharp and crisp yet still preserves the genre’s raw aesthetic. Details are impressively on display—perhaps a little too impressively, as you might find yourself turning away from those heroin injection sequences. Sound quality is similarly impressive and impediment-free. I expect these films will never look better.

Five and a half hours of content not enough for you? Have no fear, Severin has added an additional two hours of supplemental material, all of which is worth your time. The most impressive of the three featurettes, “Blood in the Streets: The Quinqui Film Phenomenon” (44 minutes), takes the viewer on an invaluable tour of the genre’s major players, relating all the extreme highs and lows that inevitably led to the subgenre’s implosion. If you don’t mind a few spoilers, you might want to watch this in advance of the films.

Up next is “Queerness, Crime, and the Basque Conflict in the Quinqui Films of Eloy de la Iglesia,” (67 minutes), a breezy, scholarly discussion that addresses the ways in which these films fit within the larger framework of LGBTQ cinema. I am pleased to see that academics have taken note of Quinqui cinema and equally pleased that Severin has included such an in-depth dialogue.

Also included is “José Sacrástan on Eloy de la Iglesia,” (8 minutes), a short interview about working with the daring and self-destructive director. You’ll also find surprisingly graphic trailers for El Pico and El Pico 2.

Given the relative obscurity of Quinqui cinema, I fear that many genre enthusiasts will give this collection a pass. Please, don’t do that. This set is not just a blu-ray release; it’s an education. You won’t regret the time spent, and you might find yourself waxing enthusiastically about a pocket of cinema that you’ve just discovered. I know I will.