Ninón Sevilla is Violeta, a vivacious dancer, or rumbera, at Cabaret Changó but is soon plagued with mistreatment and assault at the hands of the suave but ruthless pimp Rudolfo. To make matters worse, Violeta loses her job at the cabaret when she rescues a baby from a trash can and brings it into work with her. After getting fired, Violeta is eventually forced to become a prostitute to help her and the baby survive but does eventually get another job as a rumbera at club La Maquina Loca. Everything starts to go well, acquiring the safety and security of club owner Don Santiago who is willing to provide for her and her son while also becoming a popular rumbera once again. Unfortunately, Rudolfo shows up again causing trouble. Violeta must face the fact that until Rudolfo is out of the picture for good, she and her adopted son will never be able to live in peace.

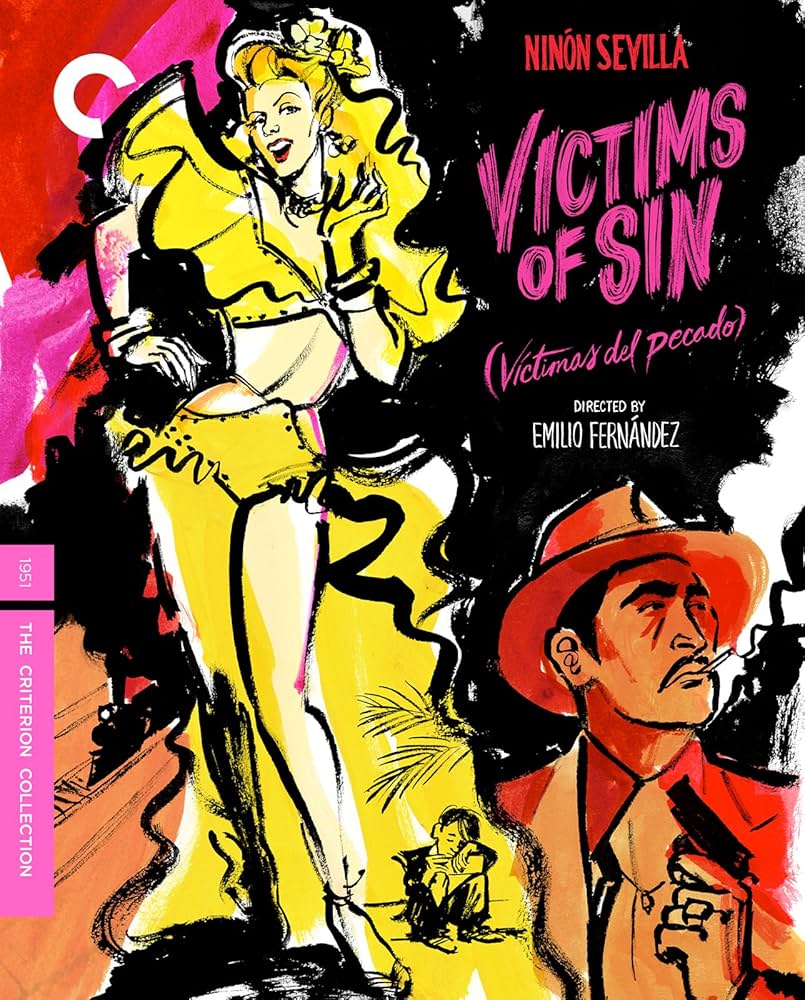

Victims of Sin is considered a seminal film in the cabaretera genre of film in Mexico during the golden age of Mexican cinema in the ’30s through ’50s. The cabaretera often took elements of the musical, film noir and melodrama to tell seedy, fiery stories of lust and betrayal with crackling rumba music and dance numbers. Victims of Sin is perhaps one of the finest examples of this style I’ve come across. Admittedly I’ve only seen a handful of these, but Victimas del pecado is significantly better than most others I’ve watched (Salón México perhaps being the only other film in the genre that could rival it). Much of the praise should go to Ninón Sevilla in the lead role who is an absolutely dynamic presence in the film. Her dance numbers are electric, and even when she is at her lowest, her eyes never lose a kind of vibrant determination to rail against circumstance. Director Emilio Fernández also elevates what could have been a tawdry soap opera into a film with a liveliness and propulsive pacing that makes it consistently engaging. Special mention should also go to cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa who delivers a beautifully shot film of deep shadows to reflect the shady morality of the characters involved. While this film does go to some very dark places with prostitution, deadly revenge and sexual abuse as recurrent themes, the way the musical numbers mesh with the bleak noir plot line is remarkable. When Sevilla begins to sing and sway, you can feel Violeta’s troubles melting away, at least for just a little while. It takes a special kind of film to pull off such a broad dichotomy of emotional resonance, but Victims of Sin does it with ease.

Criterion has delivered an absolutely stunning 4K transfer taken from the original 35mm nitrate film negative. The blacks are nice and deep, the grain is very well-balanced, and the film has a beautiful contrast that shows off Figueroa’s cinematography remarkably well. I doubt that this film will ever look better. The mono Spanish audio track is also very clean and balanced, capturing the hypnotic rumbera sequences very well. Criterion has also provided some nice extras that especially focus on the cabaretera genre and Ninón Sevilla. First is an interview with filmmaker and archivist Viviana García-Besné who provides a great deal of interesting information about Ninón Sevilla and how pivotal she was in Mexican cinema during this time period. We also get an interview with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto who gives an appreciation of Gabriel Figueroa, explaining why he was such an important and skilled DP during Mexico’s golden age. Finally we get an archival TV documentary on cine de rumberas, the cabaretera genre. Of particular interest in an interview with Ninón Sevilla on what it was like to be in these films and her role in getting them made. Additionally the disc includes a physical essay by film music expert Jacqueline Avila, and it’s an excellent piece of writing that explains how unique and important Victims of Sin was within the context of the time period.

Victims of Sin is exactly the kind of release that I look forward to from Criterion. While it’s always nice to get new 4K releases of well-established classics like Le samouraï and Picnic at Hanging Rock, when Criterion uses their clout to shine a light on great films that may be overlooked by the world cinema community at large, I always appreciate it that much more. What they’ve delivered here is an unheralded classic with a gorgeous transfer and a nice selection of meaningful extras that does the film a great service.