In Emitaï, a small Diola village is being provoked by French colonialists during World War II by being forced to give them their rice harvest as a tax imposed on them. The women of the village begin to organize and push the men of the village to take a stand against the French. One way of doing this by all the men of the village gathering for a prayer vigil to their gods, Emitaï among them. Even as the Vichy government in France gives way to the transfer of power to Charles de Gaulle, the French imperialists resort to drastic means in order to control the Diola populace.

In Xala, El Hadji Abdoukader Beye is a mover and shaker amongst the Senegalese elite, a prosperous businessman who is celebrating his success by taking on a third wife. Unfortunately for and unbeknownst to El Hadji, he has had a curse placed upon him giving him erectile dysfunction and humiliating him on his wedding night. His betrayal of his people’s traditions and customs and his embracing of a westernized, money-hungry culture has brought this ill condition upon him. But what must he do in order to gain back his manhood?

In Ceddo, the film takes place in Senegal before the era of French colonialism as Muslims, Christians and slave-traders attempt to destroy the way of life of a local tribe, designated as the Ceddo or outsiders. To protest a decision made by their king to convert to Islam, the Ceddo kidnap the king’s daughter. But can the Ceddo ever hope to reclaim their independent spirit?

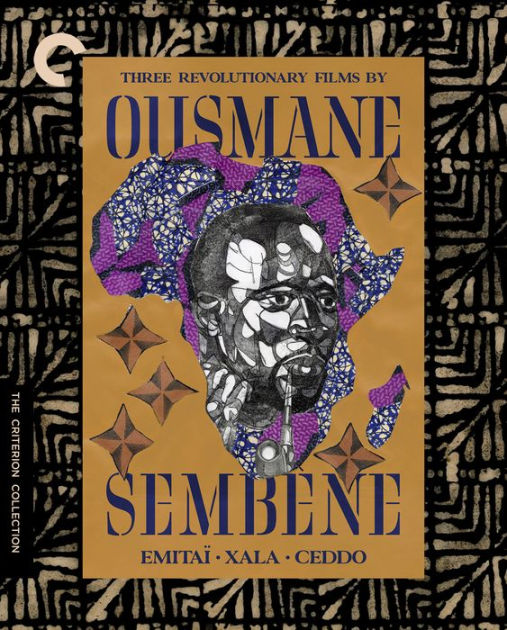

A common thread we see across much of Ousmane Sembène’s work is in his willful messaging on the dangers of allowing local culture and tradition to be superseded by encroaching modern civilization. His films are overtly political without feeling preachy. In Ceddo, the core of the film is the squaring off of the Ceddo and the Muslims as they rail against one another debating their belief structures. Sembène is patient though, giving us a steady central framing in which to allow tensions to naturally escalate. Emitaï contains perhaps the most overtly pessimistic viewpoint of the three films with a gut punch of an ending that is perhaps the most forceful in his messaging that Sembène has ever been. It definitely drives his point home, in the coldest way possible. Xala on its surface seems more comedic in tone with its potentially silly plot of a rich guy unable to get it up on his wedding night. But Sembène’s anti-encroachment themes are at the core of this film too. El Hadji has cast off his cultural heritage and beliefs in favor of money and power. A key scene in the middle of film has El Hadji meeting his daughter for a chat, and Sembène subtly illustrates the thesis of the film is this one interaction. His daughter still embraces her heritage and ancestry, refusing to drink his expensive bottled water. On the surface, they seem friendly toward one another, but his daughter’s disdain for him is evident in her every word and glance. Xala’s ending, while not as bleak as Emitaï‘s, is in some ways even more forceful in its point. Ceddo is perhaps the most bold of the three films in its revisionist aspirations with an ending that professes a triumph that may never have actually occurred based on the historical events that transpired during this time period of the 18th and 19th century Senegal. Through use of sound and visuals, Sembène is able to create a fully realized sense of time and place with a painterly directorial style reminiscent of the Italian neo-realists like Rossellini but with a more formal discipline. But despite Ceddo and Emitaï occurring in the past, Sembène infuses both films with a vitality and energy that propels them narratively. Sembène is often referred to somewhat reductively as the “Father of African Cinema”, but in many ways, he earns the title effortlessly, showcasing his efforts to use the motion picture medium to wrench away control of colonialists and build national pride.

All three films are newly restored in 4K from the original 35mm megatives, and all three look excellent. Having seen all three films before from DVD or VHS transfers, this Criterion set looks miraculous in comparison. All three films have a very soft, naturalistic color palette, although Ceddo certainly pops the most with its bright costuming. The transfers all capture a very nice balance in visual tone, and the transfers are largely free and any dust, scratches or debris that plagued previous releases of these films, although Ceddo in particular still has a little damage to the source that wasn’t restorable it appears. The audio in all three is also presented in clear, crisp monoaural tracks. The music in all three is great, a combination of jazz, funk and more traditional folk music, and the songs come across sounding full and robust. For extras, we have a few nice, meaningful segments to check out. First, included on the Emitaï disc is an interview between Mahen Bonetti, founder and executive director of the African Film Festival, and writer Amy Sall. It runs about 40 minutes and is a great discussion on Sembène’s film career and recurrent themes. On the Ceddo disc, we have a 30-minute Making of Ceddo featurette that includes some nice behind-the-scenes footage including Sembène as he edits the film. Also included is a physical booklet featuring a very good essay by film scholar Yasmina Price on Sembène’s directorial style and his impact on African cinema.

Sembène is a titan of world cinema, and this box set, while a bit light on extras, does a great job of giving us three of Sembène’s most radical and impactful films in wonderful restorations that are leaps and bounds beyond any previously available versions of these classics.