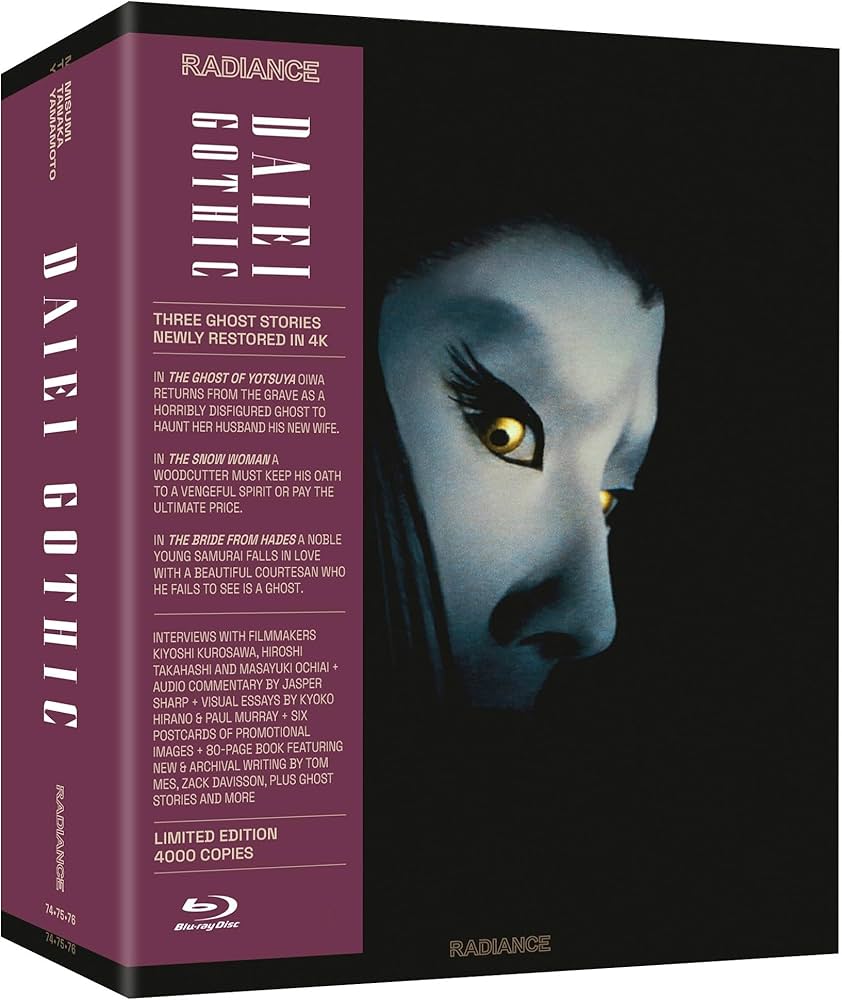

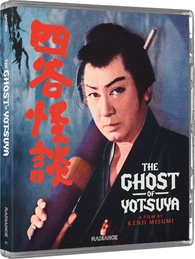

Adapted loosely from the much celebrated kabuki play, The Ghost of Yotsuya finds our lead Iemon Tamiya (Kazuo Hasegawa) destitute, having failed to become a samurai, and living with his wife Oiwa (Yasuko Nakada), depressed and aimless. One day he meets with the daughter, Ume Ito (Yoko Uraji), of a powerful samurai who becomes infatuated with him and demands he divorce Oiwa and marry her. Iemon refuses initially but is eventually misled by Ume and the devilish Naosuke (Hideo Takamatsu) which results in Oiwa being disfigured and killed. But Oiwa will return and have her vengeance!

I’ve seen a few different versions of this story over the years, and it’s interesting to compare and contrast the various adaptations. Most famously it was adapted in the same year by Nobuo Nakagawa, and that is the version I would wager more people are familiar with. That version is in some ways leaner and meaner than this version directed by Kenji Misumi which paints the lead Tamiya much more sympathetically. In Nakagawa’s version (as well as most other versions I’ve seen and read about), Tamiya is a straight-up philandering, duplicitous bastard and the story arc is more about watching him get his just desserts. Misumi’s version on the hand actually portrays Tamiya much more sympathetically, as more of a victim of circumstance who was led astray despite his obvious love for Oiwa. It’s a more emotionally complex story in some ways, particularly for the audience who is meant to take pity on Tamiya and the situation he allows himself to become entangled within. It ends up playing out as more of a ‘doomed lovers’ tale than a story of bloody vengeance. Aesthetically, the film has a nice gothic atmosphere as well that makes the ending come across as more eerie than visceral. Overall, a very nice adaptation, and I can see why director Kiyoshi Kurosawa considers it his favorite version.

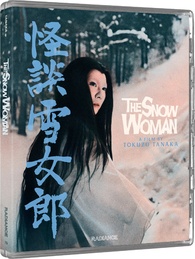

Adapted from a Japanese folk tale most famously presented in the western world as the story “Yuki-Onna” by author Lafcadio Hearn in his popular and influential book of stories Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, The Snow Woman tells the story of a sculptor Shigetomo (Tatsuo Hananuno) and his apprentice Yosaku (Akira Ishihama) who find themselves trapped in a snowstorm while searching for a tree to make a sculpture out of. They take refuge in an old abandoned shack, and during the night an evil snow witch emerges from the storm and kills Shigetomo but spares Yosaku while making him promise he must never speak of her. Five years pass and Yosaku meets and falls in love with a beautiful maiden named Yuki (Shiho Fujimura), and they have a child together. All is going well until a lecherous public official takes a shine to Yuki which sets in a motion a sequence of events that Yoksaku may soon regret.

The story of “Yuki-Onna” is another very familiar tale that I’ve both read and seen adapted multiple times, most famously as one of the four segments of Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan. While that version is rightfully heralded as an excellent telling of the story, director Tokuzô Tanaka’s longer version has much to recommend as well. Most prominently is the strikingly beautiful cinematography with certain shots, particularly toward the end, rivalling anything in Kobayashi’s film. While the pacing does flag a bit in the middle of the film, Tanaka uses the additional runtime to flesh out these characters beyond mere archetypes. This makes the ending all the more effective because we care about Yosaku. I’m intentionally trying to keep things vague so as not to spoil the story for anyone who may not be familiar with it, but I can assure you that it’s achingly tragic.

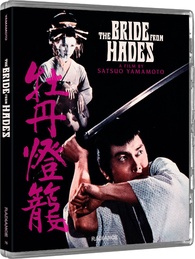

The Bride of Hades is another story most famously brought to the western world by Lafcadio Hearn as “A Passional Karma” in his collection In Ghostly Japan, although the story’s roots go much further back, originating as a Chinese folk tale from the story collection Jiandeng Xinhua in 1378. This film version tells the story of a schoolteacher named Shinzaburo (Kojiro Hongo) who has spurned his rich family’s attempts to force him to wed the widow of his brother. On the first night of the Oban Festival, celebrated by setting lit paper lanterns adrift in a stream representing the souls of the dead, Shinzaburo meets a beautiful young maiden named Otsuyu (Miyoko Akaza) and her maid after freeing a pair of peony lanterns that had become stuck in some weeds. Shinzaburo immediately begins to fall for Otsuyu but is warned by various members of the village that to be lulled into her embrace will result in Shinzaburo’s death because Otsuyu is a ghost from the underworld. But will Shinzaburo be able to resist her passionate advances?

The Bride from Hades for much of its runtime plays out more as a doomed romance than a straight up horror film (although it does have its share of creepy imagery at times as well). The film has a pervading sense of eeriness (a trait all three films in this set share) with a densely gothic set design and tone as fog banks are constantly rolling along the ground ghosts float through the air. But what you feel most is a love and a desperation both from Shinzaburo who needs a relationship that isn’t dictated to him by family and society and Otsuyu who doesn’t want to spend eternity alone. The most romantic among us may even see the ending as a happy one.

Radiance has delivered another top notch technical presentation for a trio of films that might otherwise have gotten lost to time. All three films were scanned in 4K by Kadokawa and look quite nice. The colors are vibrant when needed while the blacks are deep and clean with little to no noticeable scratches or debris in the image. The mono audio for all three films sounds nice and clean with no distortion or distracting hissing to detract from the aural presentation. The extras on this set are great and plentiful. On the Ghost of Yotsuya disc we have first an interview with director Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Pulse, Cure) who discusses why he feels Misumi’s adaptation is the best version of the story. We also get a visual essay by Japanese film expert Kyoko Hirano that discusses the various versions of the Ghost of Yotsuya and its origins as a kabuki play. On The Snow Woman disc, we get another interview with a Japanese horror filmmaker, this time Masayuki Ochiai (Shutter, multiple Ju-On films), who discusses Japanese yokai and ghosts and the differences between them. We also get a visual essay on Lafcadio Hearn by Hearn biographer Paul Murray. On the Bride from Hades disc, we get a very nice and informative commentary by Jasper Sharp and an interview with screenwriter Hiroshima Takahashi (Ringu, Ju-On: Origins) discussing the history of the folk tale that Bride from Hades was adapted from. And of course, Radiance has also included a nice, thick booklet that includes essays from Japanese film expert Tom Mes on Daiei Studios and their gothic horror output during this era and Japanese folklore expert Zack Davidsson on the history of the supernatural in Japanese literature and media. Both are excellent essays well worth a read. We also get archival reviews of all three films from the time periods in which they were released, mostly illustrating how they were underappreciated on initial release. To top it all off, we also get reprints of Lafcadio Hearn’s stories “Yuki-Onna” and “A Passional Karma” on which two of the films are based.

Radiance has done beautiful work here, producing an excellent box set of under-seen and under-appreciated classic Japanese supernatural tales that are highly worthy of rediscovery. All lovers of Japanese horror cinema owe it to themselves to check these out!