The editor of a high-profile sports magazine is looking for the next hot thing in women’s golf and sets his sights on the amateur Reiko (Yoko Shiraki) to catapult to stardom. Enlisting the aid of her manager and lover Miyake (Yoshio Harada), Reiko trains rigorously and ultimately wins her first tournament, landing her endorsement deals, a sexy bikini photo feature in the aforementioned magazine and eventually her own talk show. Soon Reiko draws the attention of obsessive neighbor Mrs. Sendo (Kyoko Enami) who begins to create all kinds of trouble for Reiko and Miyake culminating in a frenzy of humiliation in which Reiko will never be the same again.

In 1968, Seijun Suzuki was unceremoniously fired from his long-time home at Nikkatsu for producing relentlessly uncommercial and uncompromising films like Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill. After ten years in exile from the film industry, primarily only occasionally directing for television and working on writing projects, Suzuki returned in 1977 with the theatrical feature A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness for Shochiku, and while this film didn’t fare too well commercially or with critics at the time, it is in many respects classic Suzuki, an acerbic and strange story fused with eye-popping, candy bright visuals and an artistic flare that would go on to inform his later arthouse successes like his Taishō trilogy. While some may view A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness as a jumbled mess (like many critics on its initial release), I see it in many ways as the quintessential Seijun Suzuki picture, including all the trademarks for which he is known across his wide and varied career. It takes his desire to create a mood and tone with aggressive visuals in defiance of the traditional B-movie conventions by twisting the story and taking it unpredictable directions with a slice of bitter humor thrown in for good measure. We begin with a standard sports drama which by the midpoint is dovetailing into a bizarre tale of obsession and criminal acts which then zigzags again into a story of Reiko’s fall from grace in the most humiliating of ways. It’s a story of rise and ruin done in a distinctly Seijun Suzuki way. On the subject of those bright visuals, Suzuki here fully embraces that pop-art aesthetic that he delivered on so beautifully in Tokyo Drifter. From the verdant green of the golf course early in the film to the garishly colored living quarters of Reiko and her young brother Jun, Suzuki is always looking for ways to elevate the film into something beyond the normal. Interestingly the seemingly weakest aspect of the film, actress Yoko Shiraki’s stiff delivery (according to an interview in the extras, Shiraki was dating a producer of the film who demanded she star in it as a condition of his financing the picture) Suzuki turns into a positive, making Reiko’s aloofness and detachment part of her character. The always reliable Yoshio Harada plays Miyake very well, leveraging the restless, tough guy image he had cultivated over the years up to that point into this conniving slimeball of a character.

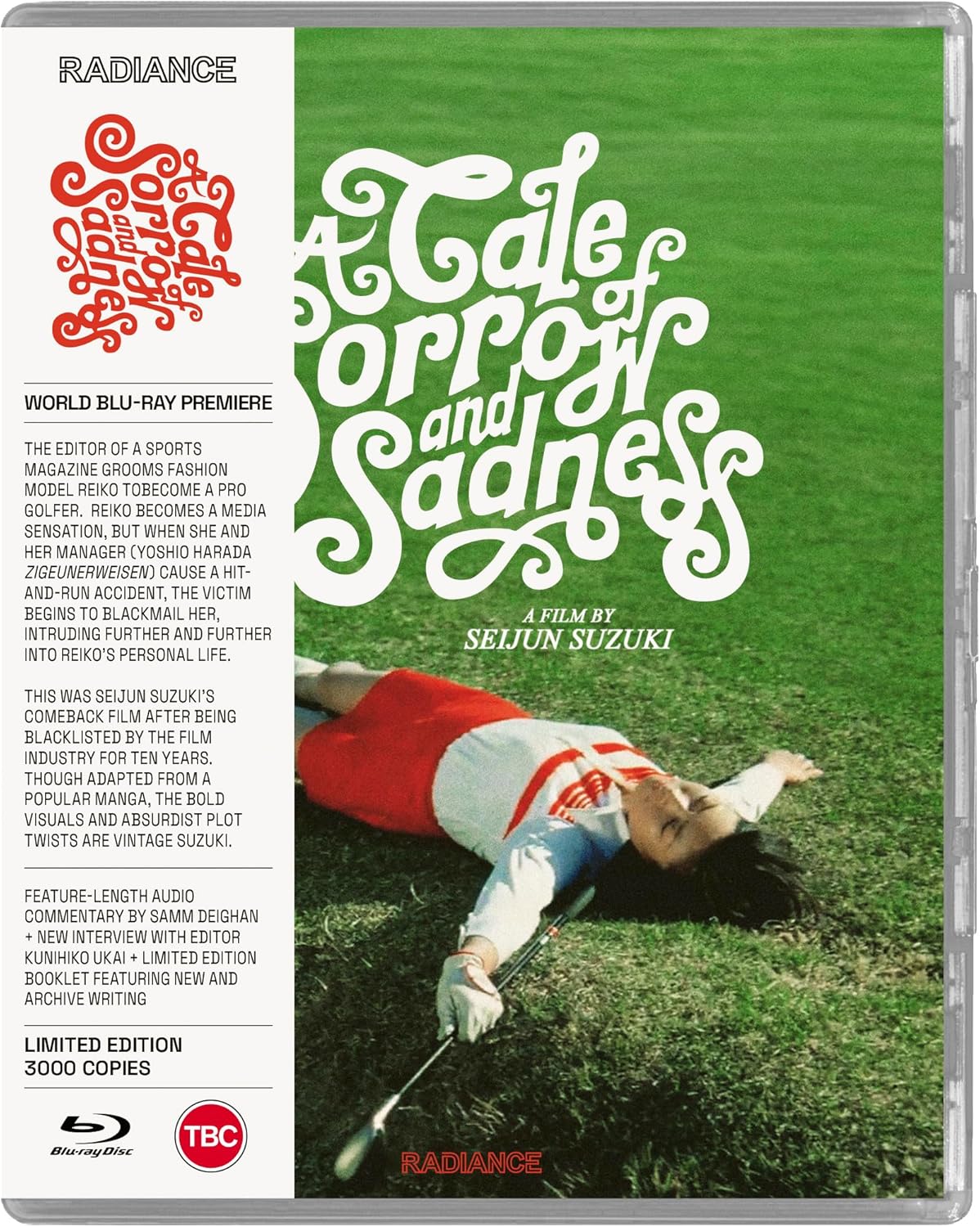

Radiance Films has delivered A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness in a beautiful high-def digital transfer provided by Shochiku. The colors are vivid without appearing oversaturated which results in a nice balance in the darker toned night scenes as well. On the audio side we get a Japanese mono track that is free and clear of any noticeable distortion or hiss and represents the film quite well. For extras, we first get an audio commentary with film historian Samm Deighan, and it is jam-packed with lots of information about the film and Suzuki’s career at this time. We also get a new interview with Kunihiku Ukai, the assistant editor for the film who gives some very candid inside info about the troubles around getting it made. The limited edition of A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, like all Radiance LEs, includes a physical booklet with a very interesting essay on Seijun Suzuki by film expert Jasper Sharp as well as a film diary by screenwriter of the film Atsushi Yamatoya which was original printed in the July 1977 issue of Scenario magazine and was translated by Tom Mes. This was a neat extra giving more of a play-by-play on how Yamatoya became involved in the production.

On its initial release, many critics found A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness to be a frenetic mess of a film. In many ways it is, but that is what I find so fascinating about it. It’s an unfettered Suzuki trying to get as many ideas out there as possible after a ten-year drought. This is easily one of my favorite Seijun Suzuki films, and Radiance has delivered it with a great transfer and some nice, informative extras that makes this an easy one to highly recommend!