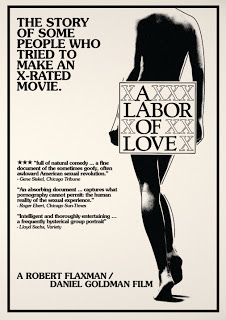

In A Labor of Love, the makers of an independent-financed drama titled The Last Affair are compelled by their backers to shoot hardcore sex scenes for the movie to ensure it has a better chance of recouping their investment. This request does not initially sit well with director Henry Cheharbaschi and his cast (including Deborah Dan, Jerry Goodman, and Ronald Dean), but they soldier on with the filming of the explicit love scenes in the hope that they can adapt the mercenary endeavor to their artistic sensibilities. Quickly they realize that this is an impossibility because despite the best efforts of all involved no one on the cast and crew has any experience making pornography. The actors are awkward around each other, with the women feeling degraded and the men unable to perform in the sack while the cameras roll. All the while a documentary film crew records the proceedings falling apart. Creative compromise is hardly a foreign concept in the film industry. Most of the time it is essential to making a worthwhile product. Filmmaking, after all, is a collaborative art form and every person’s opinion, from the director to the writer to the producer to the actors to the cinematographer to the sound technician to the prop department to the catering crew, has to matter even if they aren’t applied in the end. Compromise is practically forced upon you when you have no other choice. You might be a struggling independent filmmaker making their first feature or a young, idealistic director who just signed to helm a big-budget tentpole blockbuster for a major studio. In both of those situations the phrase “complete creative control” will be heard as much as “low-cost healthcare for all Americans” at the annual Conservative Action Political Conference. Remember that scene in Ed Wood where Ed went to slaughterhouse owner Rance Howard for money to make Bride of the Atom and Rance agreed to do but only on several conditions? You know, like renaming the movie, adding a nuclear explosion at the end, and casting his no-talent son in the male lead? Yeah, that may sound hilarious when you see it in a movie, but many enterprising filmmakers could tell you their own horror stories about dealing with intrusive producers, financiers, studio executives, actors, writers, etc., and the hard road they had to travel just to get their long-in-the-works movie a day-and-date Video On Demand and Blu-ray release. When I first heard of A Labor of Love I naturally assumed it was a “mockumentary” about the making of an adult film because I had never heard of The Last Affair, the feature whose making is partially documented here. No, The Last Affair is indeed real and Labor is the story of how the film’s producers demanded the intimate drama about relationships in free fall be reshot and reedited into a XXX flick, an idea that was ultimately abandoned when the Chicago-lensed Affair finally opened and closed quietly in October 1976. Roger Ebert panned Affair while it played but actually gave Labor a recommendation when it opened several months before. So lousy was The Last Affair’s reputation that its backers had to purchase a theater just to get it some play (the Chelex, formerly the Playboy Theater). It sounds like a pretty bad movie I have no desire to ever see. After watching A Labor of Love once I felt like I’ve already viewed the best parts of The Last Affair, the parts that were ultimately left on the cutting room floor. It isn’t a rare case when pornographic sex scenes hold the power to improve a movie, but the people involved with the making of The Last Affair don’t know the first thing about making a hardcore flick. Sure, they know plenty about sex and intimacy and all, but to bare their bodies and copulate on celluloid is a whole different beast. The actors are professional and give it the old college try though. Problem is, pornography requires several levels of detachment they aren’t able to reach. They make desperate attempts to approach the new scenes from creative and emotional perspectives, which is very possible but something they struggle to make sense of when they’re really in the moment. The actors go out on the town and enjoy each other’s company in the vain hope that it will translate into sexual chemistry once the cameras roll. It all backfires horribly. There’s a reason why The Last Affair was ultimately released sans the graphic love scenes that the producers had pinned their hopes of a prosperous box office return on they probably just as much as the movie itself. A Labor of Love co-directors Robert Flaxman and Daniel Goldman were given unprecedented access to the filming of the new scenes and conducted extended and blunt honest interviews with director Cheharbaschi and several of his reluctant performers. All of the participants in this documentary give thoughtful and candid insights into sexuality, relationships, and their gradually evaporating disinclination to having sex on screen. Some of the interviews are worth watching, though the overall pace of the movie is plodding despite having a running time of merely 67 minutes. We get endless behind-the-scenes footage of the attempted filming of the sex scenes and the interviews also tend to run from beginning to end without the benefit of a little imaginative editing. The nudity is explicit but there isn’t anything on display here to placate the raincoat crowd. The human soul is what is being stripped to the bone, and that is more than enough once you watch A Labor of Love. Vinegar Syndrome has given A Labor of Love the first-class treatment for its home video premiere. The film has been lovingly restored from the 16mm camera original, scanned in 2k resolution, and presented in anamorphic widescreen in its 1.85:1 theatrical aspect ratio. Though the transfer does not have me jumping for joy it is good enough to give high marks to Vinegar Syndrome for doing the best job they possibly could with the elements at their disposal. The picture quality is very soft but print damage only rears its unattractive head on rare occasions and the grain content is also kept to a minimum to maintain the documentary quality of the film. We get an English 2.0 audio track with the film that features some unavoidable instances of minor audio distortion, and often the overlapping dialogue sounds garbled, but for the most part, this is a better than decent mix that at the very least doesn’t have any glaring signs of permanent damage that detracts from the viewing experience. No subtitles are included. The best extra is a Q&A session with co-director Flaxman (37 minutes) that was filmed following a screening of A Labor of Love and features a lot of background info and production anecdotes regarding the movie’s making. Lastly, we get a theatrical trailer. An audio interview with Flaxman and John Iltis that was listed on the company’s website as part of the bonus features was not included here. A Labor of Love, a candid and infuriatingly dry peek behind the curtain at the making of a porno that was never by people who had not the slightest idea how to stage or perform in one, is certainly one of the best movies resurrected and set free in the home entertainment realm by Vinegar Syndrome. One viewing of this movie might put you off porn for a few years, or give you a newfound appreciation for people who work or have worked tirelessly in the adult industry. Either way, A Labor of Love is worthwhile. Director – Robert Flaxman, Daniel Goldman Cast – Henry Cheharbaschi, Deborah Dan, Jerry Goldman Country of Origin – U.S. Discs – 1 Distributor – Vinegar Syndrome Reviewer – Bobby Morgan Original Post Date – 06/26/13 |