In this seemingly never-ending installment of my journey through a big ass list of horror novels, I tackled a zombie novel that harnesses the power of bloggers to chronicle a conspiracy, an austere Victorian-style gothic thriller with a dark comedic streak, a weird and funky were-something pulp novel, a fiery collection of Argentine horror short stories and another massive tome of supernatural fiction.

For those just joining me, this is my journey through the following “Best of” Horror lists:

Reedsy Discovery Best Horror Books

Stephen Jones & Kim Newman’s Horror: 100 Best Books

Stephen Jones & Kim Newman Horror: Another 100 Books

If you want to check out my previous entries, they can be found here:

Part 22 | Part 21 | Part 20 | Part 19 | Part 18 | Part 17 | Part 16 | Part 15 | Part 14 | Part 13 | Part 12 | Part 11 | Part 10 | Part 9 | Part 8 | Part 7 | Part 6 |Part 5 | Part 4 | Part 3 | Part 2 | Part 1

Now hop nekkid on your were-tiger and join me for some fun fiction!

Feed (Mira Grant, 2010)

List: NPR & Reedsy Discovery

Georgia Mason and her brother Shaun are news bloggers in a world where the victims of a new virus causes the dead to reanimate and the living to potentially immediately turn if infected. The Mason siblings have snagged an amazing opportunity as official bloggers of the Senator Ryman campaign to run for president, but what they don’t realize is that zombies are far less dangerous than the shadowy conspiracy they begin to uncover that threatens to drive the nation into a very scary place.

Feed is one that I have a lot of mixed feelings on. It had a very nice sense of world-building and has some genuinely interesting ideas that elevate it beyond the typical “survival the zombie apocalypse” story including its “All the President’s Men” style political conspiracy plot. Grant is also capable of a compelling sequence when she wants to and isn’t bogging us down with needlessly repetitive sequences of blood testing (which happens almost constantly here). Also while like I said the world building is actually quite good, really fleshing out how this world functions in a post-zombie society, Grant’s character development on the other hand is pretty thin. The main character Georgia seems too kool for skool and her brother just sounds like an obnoxious frat guy most of the time. You’ve got the plucky sidekick (their tech wizard Buffy) whose only unique characteristic is that she’s religious which naturally comes into play in the plot. Senator Ryman is your pretty standard idealistic (and non-existent) upstart politician who just wants to make the world a better place, and Governor Tate (ultra conservative southern racist asshole) is such an obvious evil guy that she might as well have named him Mr. Burns. The book also relies on a kind of twist 2/3 of the way through that I felt was kind of cheap in a way for reasons I can’t really explain without major spoilers. I think with a better editor who could’ve pared down some of the repetitiveness of the book and who could’ve filed down the somewhat aimless middle section and if Grant had invested more time in character building, this could’ve been a lot more compelling than it was. As it is, it’s still quite readable and is a fairly effortless one to dig into despite its flaws.

The Grotesque (Patrick McGrath, 1989)

List: Jones/Newman

We find Sir Hugo at the start of this sordid gothic mystery wheelchair bound, paralyzed from the neck down and even unable to speak or indicate that’s able to produce coherent thought. But we know he’s thinking. Sir Hugo recounts the story of what brought him to this point. All his suspicions of his new butler Fledge, his suspicions of murder, of carnal relations with Sir Hugo’s wife, of blackmail and of the position in which Sir Hugo finds himself. Sir Hugo’s paranoia goes deep. It all starts with the disappearance of Sidney, the foppish beau of Sir Hugo’s daughter Cleo. And when Sidney’s bones are found pig-gnawed, Sir Hugo can only watch in abject disappointment as his loyal gardener George is tried for the crime while Sir Hugo seethes with vindictiveness, knowing that it’s all Fledge’s doing.

This was a delightfully macabre old school gothic tale in the grand tradition of McGrath’s forbearers of the Victorian period complete with mysterious doings on the fog-drenched moors while also paying tribute to more recent dark gothic melodramas such as Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle and the sordid family troubles of V.C. Andrews. The Grotesque also has a sly sense of dark humor pervading the proceedings as we follow the highly unreliable first-person narration of Sir Hugo such as imagining Fledge mounting his wife in the pantry. The story jumps back and forth in time and Sir Hugo’s memories and recollections spew forth in a kind of austere mish-mash. McGrath does a very good job of getting in Sir Hugo’s headspace while constantly sewing seeds of doubt as to what’s real and what’s not. In a way this fractured narrative creates some ambiguities that may frustrate some of the more factual-driven folks out there and the pacing is a little stop-and-go at times because of the narrative style. Still, I think this is a very solid work that should prove to be satisfying for those looking for a more contemporary ancestor of the classic gothic fiction of an era gone by.

Darker Than You Think (Jack Williamson, 1940)

List: Jones/Newman

Grizzled reporter Will Barbee is on his way to the airport to get a scoop on a potentially revelatory archeological find his former mentor Professor Mandrake is bringing back from some ancient Mongolian ruins. Along the way he runs into sexy young reporter April Bell who coaxes Will into joining him for the announcement. Despite heightened security and a general sense of paranoia, Professor Mandrake is seized by a sudden mysterious ailment while delivering his announcement and dies on the spot. Did April Bell have something to do with the professor’s death? What is the mysterious object in the box that the professor brought back from the expedition? As Will digs deeper to find out what’s happening, he discovers a whole underworld of dark magic and shapeshifting that kicks off a series of strange and terrible deaths that Will may be right at the center of.

Well, this was a pretty bonkers book. I’ve heard this multiple times referred to as a werewolf book which I suppose it has that as an elemement, but it’s really more a witch/black magic story with multiple shapeshifting elements. You’ve got werewolves, yes, but also a were-sabretooth tiger, a were-snake, etc. In addition, the explanation for how these were-creatures live and operate is some of the most insane pseudo-scientific lunacy I’ve read in a while. Something about using probability to move between the atoms while astral projecting? I dunno. With this one, you just kinda have to accept the insanity and go along for the ride. It really is a lot of fun despite being totally preposterous. Really the biggest issue I had with it is just how obtuse the main character of Will Barbee is. He is constantly confronted with crazy stuff, from April Bell telling him on their first date that she’s a witch to transforming into multiple animals and murdering people, and he just obstinately refuses to even entertain anything supernatural occurring until extremely late in the story. Also the ending was pretty easy to see coming. Despite all that though, I did enjoy this wacky, pulpy occult horror book.

Things We Lost in the Fire:Stories (Mariana Enriquez, 2017)

List: NPR & Reedsy Discovery

This short story collection from Argentine writer Enriquez is a kind of mix of dark urban horror in the vein of Ramsey Campbell mixed with socially conscious literature and the more psychological and societal terror of Shirley Jackson. In general the stories are quite good with some being better than others but overall worth checking out.

Perhaps the best story in the collection is “Under the Black Water”, the tale of a prosecutor looking into the murder of a couple of boys by a pair of corrupt cops that leads her into the slums of city where she becomes immersed in a mysterious cult. While some of the stories in this collection go for more visceral shocks, this one is all slow burn creeping dread steeped in folk horror and is well worth the read. Like “Under the Black Water”, several stories here deal with the clash between the middle and lower classes like “The Dirty Kid” (which was interesting but petered out at the end a little) and “The Neighbor’s Courtyard” (I wasn’t very clear what this one was even trying to say… I ended up feeling mixed about it). Some of the stories are a little more traditional in their telling like “The Inn” which felt like something out of an Alfred Hitchcock Presents, “Adele’s House” a suitably creepy haunted house story, and “An Invocation of the Big-Eared Runt”, a story of a tour guide who gives murder tours that finds his tour subject matter a little more uncomfortably close than he’d prefer. Others were bizarre and unsettling like “End of Term” (another with a gotcha kind of ending) and “No Flesh Over Our Bones”, a weird one about a woman obsessing over a human skull she found. The titular story “Things We Lost in the Fire” was honestly I thought a little weaker than some of the others, coming across much more overtly political and heavy-handed than any of the others. I thought this approach blunted the author’s intent of weaving subtle layered messages throughout the stories and the fact that it’s the last story in the collection also causes one to leave the book with a very different idea of tone and message than the majority of the collection conveyed. Despite that, overall I liked this one in general and think it’s worth a look if you dig legit horror stories with an interesting and unique worldview.

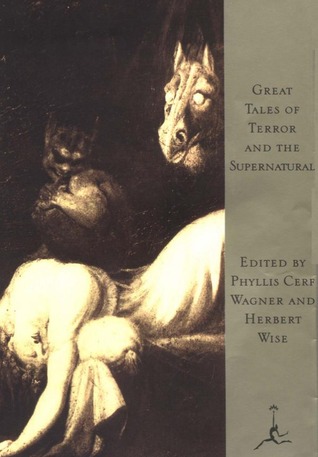

Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural (Edited by Phyllis Fraser & Herbert Wise, 1944)

List: Jones/Newman

Here we have another mammoth 1000+ page anthology segmented into “Terror” (non-supernatural tales of murder and suspense) and “Supernatural” with, as the editors themselves point out in the intro, “Terror” getting the short shrift in comparison to the bevy of ghost stories taking up space. On the Terror front, we have much anthologized and beloved stories such as Poe’s “The Black Cat” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar”, Ambrose Bierce’s “The Boarded Window”, Saki’s “Shredni Vashtar” and Richard E. Connell’s highly influential “The Most Dangerous Game”. It also includes stories from authors not normally associated with genre fiction like Thomas Hardy (“The Three Strangers”), William Faulkner (“A Rose for Emily”) and Ernest Hemingway (“The Killers”), and while none of these would ever be classified as horror, they do all share a dark and macabre footprint that doesn’t make them feel out of place in this compendium. Also in Terror we have some lesser known gems like W. W. Jacobs’ “The Interruption” (whose much more well-known “The Monkey’s Paw” will make an appearance later), H.G. Wells’ lesser known “Pollock & The Poroh Man” (which I would argue should’ve been in the Supernatural section) and the epically suspenseful “Leningen Versus the Ants” by Carl Stephenson.

The Supernatural section which comprises roughly 2/3 of the book kicks off in fine fashion with Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s creepy and atmospheric “The Haunters and the Haunted: or, The House and the Brain”. Unfortunately it includes an extended epilogue not present in previous editions that really bogs the story down, and it’s easy to see why Lytton excised it from prior versions. In addition we have several stories that we’ve seen many times before and since in other anthologies (mostly with good reason) such as Fitz-James O’Brien’s “What Was It?”, “The Horla” by Guy de Maupassant, F. Marion Crawford’s “The Screaming Skull”, Saki’s “The Open Window”, “The Ghost Ship” from Richard Middleton and “Afterward” from Edith Wharton. It also includes two of M. R. James’ heaviest hitters with “Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” and “Casting the Runes”. It also includes not one, not two but THREE major novellas: “The Great God Pan” by Arthur Machen, “How Love Came to Professor Gildea” by Robert Hitchens (which was a solid story but honestly felt too drawn out) and Oliver Onions’ classic “The Beckoning Fair One”. Other standout stories include Algernon Blackwood’s “Confession”, the fantastical grim whimsy of E.M. Forster’s “The Celestial Omnibus” which is like a Magic School Bus episode gone dark, the hauntingly sad and surprisingly subtle “They” from Rudyard Kipling as well as as some favorites I had read previously like Benson’s creepy crawly “Caterpillars” and Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror”. All in all, this is a suitably stacked horror anthology excellently curated with lots of great stories for both seasoned horror fans and newbies looking to dive more into the history of supernatural fiction.