Been a long time, folks! It’s Boo month, so I thought I’d get one of these horror write-ups out into the wild for people to chew on a little. In this batch we have an incredibly bizarre sci-fi cult classic, a collection of Appalachian cryptid horror tales, a long-dark neo-noir into film nightmares, another seminal collection of horror short stories from legends in the business and a modern classic vampire tale from Sweden. Fun stuff is afoot!

For those just joining me, this is my journey through the following “Best of” Horror lists:

Reedsy Discovery Best Horror Books

Stephen Jones & Kim Newman’s Horror: 100 Best Books

Stephen Jones & Kim Newman Horror: Another 100 Books

If you want to check out my previous entries, they can be found here:

Part 30 | Part 29 | Part 28 | Part 27 | Part 26 | Part 25 | Part 24 | Part 23 | Part 22 | Part 21 | Part 20 | Part 19 | Part 18 | Part 17 | Part 16 | Part 15 | Part 14 | Part 13 | Part 12 | Part 11 | Part 10 | Part 9 | Part 8 | Part 7 | Part 6 |Part 5 | Part 4 | Part 3 | Part 2 | Part 1

Be kind. Please rewind.

A Voyage to Arcturus (David Lindsay, 1920)

List: Jones/Newman

Maskull, at the invitation of his friend Nightspore and a man named Krag, decides to partake of interstellar travel and journey to the planet of Tormance. Upon arriving via some weirdness involving crystals and a “back ray”, whatever that is, he finds that his acquaintances are nowhere to be found. Despite that, he sets off on a journey across Tormance, experiencing allegorical situations that provide a mechanism by which author Lindsay shows the relativism of good and evil, using them as a springboard for philosophical considerations. Not only does it explore the ideas of morality but also gender fluidity and spirituality. Maskull meets along the way a variety of odd characters. There’s Joiwind and her husband Panawe who embrace nature and refuse to harm a single living creature, animal, plant or otherwise. There is the bold and lustful Oceaxe who desires Maskull to kill her husband. There’s Tydomin, a woman who kills Oceaxe and manipulates Maskull into committing atrocities. There’s Earthrid, a man who lives on an island, playing a musical instrument every night that is rumored to kill all who experience it. There’s Leehallfae, an air-based being of a third sex who journeys with Maskull to the underground country of Threal. There’s Haunte a man whose masculine stones repels the intense and deadly feminity of the realm in which he dwells. There’s Sullenbode, whose kiss kills Haunte and who Maskull falls in love with. As Maskull travels through the various environments, his bodies changes to adapt to the people around him, growing a tentacle from his chest that experiences love more deeply, growing additional eyes, a third arm as well as mysterious organs that do not exist in our reality in order to more richly experience the world around him including the two additional colors not found on Earth.

A Voyage to Arcturus is easily one of the more singularly strange novels I’ve read in a while, particularly for the time period in which it was printed. Structurally it’s something of a mess, highly episodic and willfully confusing at times. But the richness of the world-building is undeniable. Lindsay shows an impressive imagination in service of introducing some fairly heady ideas of the nature of existence and moral relativism. Maskull as a character is something of a blank slate, taking on the traits needed for the situation. Gracious and considerate one moment, petty and wrathful the next, Maskull is less a person than a vehicle for the ideas Lindsay wants to illustrate. but based on the ending, maybe that’s the point? Regardless of this willfully bizarre tale’s philosophical merits, A Voyage to Arcturus stands as what I imagine to be a quite influential work in the realm of fantastical sci-fi. C. S. Lewis has talked about it being one of the primary influences on his Space Trilogy and Michael Moorcock has sang its praises as well. In regards to its place on a Best Horror list though, the inclusion is dubious at best. While it does begin with a seance (which we will revisit later in the book) and includes some horrific sequences of murder and death, it’s mostly very much a fantastical sci-fi novel structured like Pilgrim’s Progress. Overall, I found it pretty interesting, but I can definitely see how this one more than many I’ve read is a very niche book.

Owls Hoot in the Daytime & Other Omens (Manly Wade Wellman, 1951-1987)

List: Jones/Newman

One of Manly Wade Wellman’s most endearing creations over the years has been his Appalachian folk balladeer, confronter of the uncanny, Silver John. This collection of stories (which includes all of the stories included in the Arkham House collection Who Fears the Devil? that was profiled on the Jones & Newman list plus several others more recent) offers a very entertaining mix of homespun folk wisdom, strange horror from the hills, weird unearthly cryptids and simple people caught in the middle of it. John the Balladeer is both a conscientious objector at times, observing the terrors without actively seeking to disrupt what’s happening (as in stories like “The Desrick on Yandro ” where he’s content to follow and not interfere), and at other times is more a man of action, diffident but agreeable and ready to wallop an ugly bird (in “O Ugly Bird!”) or face down dark terrors that lurk in a forbidden cavern (“Owls Hoot in the Daytime”). Much of the time, John’s inquisitive nature and cheerful disposition, ready to sing a song or sit a while and chat with the locals, is strikingly infectious, making the stories very easy reads to be sure despite a somewhat predictable story structure for many of them. The exceptions are stories involving a girl named Evadare who John rescues from the clutches of a sinister warlock and who he eventually makes his wife after she shows her brave selflessness in eating the sins of another. These stories show a kind of continuity (that carries on into the novels from what I gather) that many of the more episodic encounters don’t.

Wellman shows a kind of genius inventiveness in concocting a kind of mix of Appalachian folk tradition with his own made up monsters and legends that blend seamlessly with one another to the point that any of his inventions could have easily come from actual stories passed down from North Carolina ancestors spoken and sang over an open campfire in the company of friends. I enjoyed these stories quite a bit with Wellman’s prose being a perfect balance of folksy without mawkishness or insult. And he has a way of describing people, places and (especially) things very vividly and memorably which makes for a really fun set of stories to dive into. Having said that, I would suggest maybe spacing them out a little to avoid them feeling a little overly same-y at times.

Night Film (Marisha Pessl, 2014)

List: Reedsy Discovery

Scott McGrath is a disgraced investigative journalist who had printed a story based on a seemingly false lead about the enigmatic film director Stanislas Cordova. When Cordova’s 24-year old daughter Ashley is found to have committed suicide under mysterious circumstances, McGrath is drawn into an increasingly deepening story, trying to piece together the days leading up to Ashley’s death reluctantly with the help of a young actress wannabe Nora and a skeazy drug dealer Hopper, both of whom knew Ashley before she died. Before long they’re running through the halls of a mental hospital, trying to ward off black magic curses and trying to discover what was at the heart of the director Cordova’s mysterious essence that could shine on a light on what happened to Ashley.

Night Film is not what I would call high art, as it posits the films of fictional director Cordova (although honestly based on the descriptions, I question how great these movies are actually supposed to be). But I will say that it’s a fun and generally briskly paced thriller that doesn’t feel overly long despite being over 600 pages. The structure is not unlike that of Citizen Kane, a reporter trying to piece together the life story of Ashley Cordova to understand her motivations by speaking to the people close to her and her father. But really it’s about his persistent desire to understand her father, the director. To find the truth of who he was and what he did. At times, with Nora and Hopper in tow, it feels a little like an ersatz Scooby gang, rushing into the thick of things with a nose for clues. While Scott, Nora and Hopper get some development over the course of the book, they ultimately feel a little more one-dimensional. Much more fleshed out is the character of Ashley Cordova with each bit of new information further deepening our understanding of her while the understanding of her father seems to grow even more obfuscated as the novel goes on. While I knock authors like Dean Koontz for their one-dimensional writing, I honestly don’t mind some archetypal short hand if it is in service of something interesting (and frankly Koontz seems to rarely have anything interesting to say). Much of this book plays out like an occult mystery, not unlike Hjortsberg’s Falling Angel but the truth behind what really happened is much more murky here. And yet, it didn’t feel unsatisfying by the end either. Overall, I enjoyed this one, likening it to a popcorn thriller you’d see over the summer. It’s not always amazing, but it’s rarely boring.

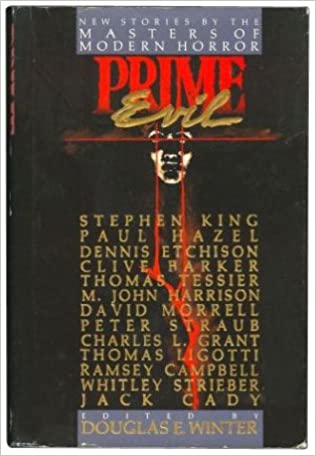

Prime Evil (Edited by Douglas E. Winter, 1988)

List: Jones/Newman

Prime Evil is a horror anthology that seems designed mostly for those of a more subtle temperament. Many of these stories seem to aspire to something more literary, and they are rarely openly shocking or graphic from a violence standpoint. The story that I’m sure caused many folks to pull the trigger on this collection is the first appearance of Stephen King’s “The Night Flier” which is King sort of riffing on Kolchak, Night Stalker territory but with a lead character far more sleazy and unlikable. It’s an ok, pulpy story but not really one of King’s best, to be honest. This is followed by “Having a Woman at Lunch” by the only writer in this collection I’ve never heard of, Paul Hazel. Frankly this one is kind of a dud and feels very creaky and silly. Quite out of place in this collection. “The Blood Kiss” by Dennis Etchison is a pretty fun story for the most part but he doesn’t really stick the ending. We also have a Clive Barker story, the sorrowful and languidly paced “Coming to Grief”. It’s well written but almost too nuanced for the average horror fan. “Food” by Thomas Tessier is one of the better stories here just in how strange and grotesque it is even though tonally it doesn’t fit that well with many of the other stories. M. John Harrison’s “The Great God Pan” was just kind of a mess of a story that falls flat. David Morrell’s “Orange Is for Anguish, Blue for Insanity” is I think the best story in the collection, a nicely paced story of an artist gone mad and his effect on anyone unfortunate enough to look too closely at his work. It actually reminded me of the similarly themed Night Film that I just finished. “The Juniper Tree” by Peter Straub is easily the most disturbing story here, graphically depicting the sexual abuse of a kid in a movie theater. It certainly isn’t horror in the traditional sense but is definitely horrific. The story itself is very well-written but sticks out like a sore thumb in a collection like this. Charles L. Grant’s “Spinning Tales with the Dead” has a nice atmosphere and some interesting ideas but doesn’t feel cohesive enough as an actual story to work for me completely. “Alice’s Last Adventure” by Thomas Ligotti is a solid one that certainly captures the flighty oddness of Alice in Wonderland while taking it to a more wistful, melancholy place. Ramsey Campbell’s “Next Time You’ll Know Me” is a decent and mildly amusing sort of meta story but feels slight in comparison to many of the stories here with heavier themes. Whitley Strieber’s “The Pool” is actually quite haunting and effective despite the extra-terrestrial influence of seemingly everything Strieber’s done since Communion. Jack Cady’s “By Reason of Darkness” is one that I felt like I wanted to like more than I did. The structure is spotty and it feels far too drawn out in places with its The Deer Hunter meets Pet Semetery tone that it seems to be going for.

Overall I think Prime Evil is a solid anthology but certainly not one of the best I’ve read with the best stories by David Morrell (creator of RAMBO), Thomas Ligotti, Thomas Tessier, Clive Barker and (surprisingly for me at least) Whitley Strieber and with writers like King, Straub and Campbell that I normally really like just not quite delivering what I wanted by either going too far afield or putting forth less than stellar work.

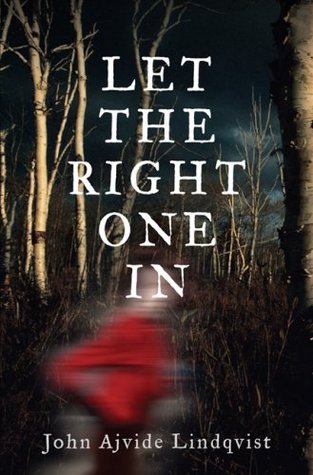

Let the Right One In (John Ajvide Lindqvist, 2004)

Lists: NPR & Reedsy Discovery

12-year-ld Oskar is an odd, insular kid with from a broken family with a fixation on murders and a knack for getting bullied. A girl his age named Eli has move in next door and before long, he befriends her, despite her odd habits like seemingly being out of touch with modern pop culture things like Rubik’s Cubes and keeping night owl hours. Eli has a secret. She drinks blood, needs it to survive in fact. Otherwise she finds herself growing more and more pale, wasting away, transforming into something else, something with long claws and sharp toes. Living with Eli is who appears to be her guardian, a man named Håkan, who might be responsible for the recent outbreak of murders in town with his own disgusting secrets he harbors. A local drunk named Lacke slowly starts to catch on to what’s happening though after his friend Jocke goes missing and eventually is found dead. Things begin to escalate even further when his on-again, off-again girlfriend Virginia is attacked one night while walking in the park by something small, dark and fast. After Lacke rescues her, she begins to exhibit strange symptoms, skin boiling in the daylight punctuated with unusual cravings. How will Oskar react when he finds out Eli’s secrets?

Having seen both film versions of this novel (and liking both quite a bit), I was already quite familiar with the overarching story and characters. Having said that, the book is much more lurid and pulpy than either of the films with Håkan’s disturbing predilections much more explicit than implied in particular. The films also mostly remove Eli’s back story and true nature which makes sense in the context of the films but adds an interesting dimension to the novel. The book also spends more time on secondary characters, fleshing out the town of Blackeberg and its denizens more than the films have time to. Despite its relatively long length, the book is a fairly breezy read, at times moving at a nice pace with some very good character development. I do feel like there are times as well where the book spins its wheels a little, losing focus on what it wants to say and feeling like more a collection of subplots than a singular cohesive narrative. Overall I thought this book was quite good and earns its place in the greater pantheon of well-executed vampire literature despite some inconsistencies in pacing and tone in a few places.