Clément (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is living a double life. Unbeknownst to his former actress wife Anne (an always ethereal Romy Schneider) in a marriage ranging from shaky to actively hostile, he is secretly a right-wing terrorist. Clément is forced to flee the city with Anne after a botched assassination attempt. He heads to the countryside and hides out with an old friend of his Paul (Henri Serre) who knows nothing of Clément’s more violent proclivities. Soon Clément leaves Anne in the care of Paul to handle some unfinished business, and Anne finds herself drawn to Paul’s more kindly, pacifist nature, in direct contrast to Clément’s brutish and violent fascist tendencies.

Le combat dans l’ile was Alain Cavalier’s first film but shows a confidence and sure hand of a director much more experienced. Cavalier had begun his career working in film production, eventually serving in an assistant director capacity to Louis Malle on Elevator to the Gallows and The Lovers. And it’s no surprise that Le combat certainly has a similar feel to those two Malle films, balancing romanticism with a more stark realist tendency and infusing it with a political subtext. This film has an interesting structure in that it feels like two halves of two very different films. In the first half, it plays out like a noirish political thriller as Anne begins to suspect Clément may be hiding a dark secret from her (and yea, finding a bazooka in your closet is a pretty safe indication that he’s up to something). The cinematography is excellent here with a smoky effervescence that casts Romy Schneider as an angel among devils. After they flee to the countryside, the film shifts into a more conventional romantic drama with only touches of the thriller elements from the first half. While this may seem on the surface a tonal inconsistency, the through-line is Anne herself and her journey of rediscovery, once suppressed and closed off by Clément now allowed to blossom away from the claustrophobic and dangerous life she had been living. She not only finds a sensitivity in Paul completely lacking in Clément, but she also reignites her film career which Clément refused to let her continue after they were married. As such, by the end we see Anne navigate from Clément’s woman to the true Anne, finally able to see a light at the end of a once very dark tunnel.

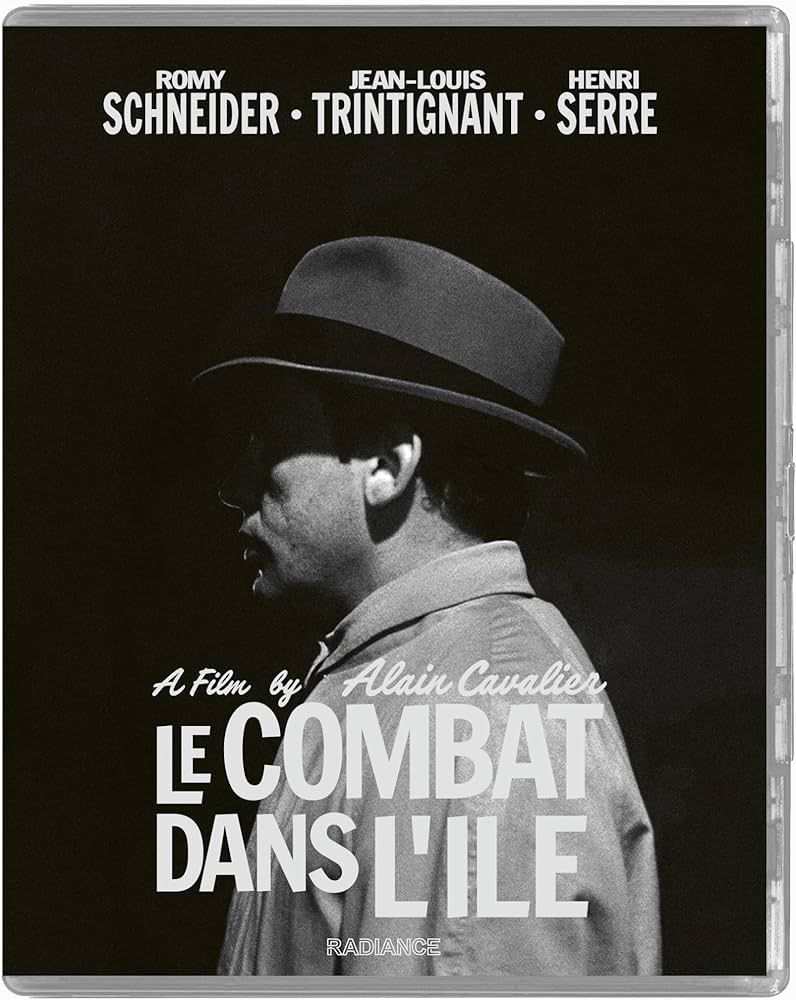

Radiance has provided a very nice 2K restoration of the original elements which showcases the wonderful cinematography by Pierre Lhomme (who would later go on to shoot Melville’s gorgeous Army of Shadows) here quite well. On the audio side we have the original French mono track which comes across nice and clear. As usual, Radiance includes a healthy dose of informative extras that help add context to the film in several different ways. First we have several interviews including a couple with direct Alain Cavalier who is quite candid about what it was like working with Romy Schneider at a point in her career when she’s starting to pivot from teen darling of the Sissi movies to serious dramatic actress. We also have interviews with the French film critic Philippe Roger as well as star Jean-Louis Trintignant. Also included are two short films from Cavalier, Un Americain and France 1961. France 1961 is more of a featurette made by Cavalier about Le combat dans l’ile, showing production stills from the film while Cavalier discusses it in voiceover. Un Americain (or L’americain in some places) is a solid first effort from Cavalier, the story of a sculptor living in the margins in Paris. It showcases that same style of Cavalier’s that finds itself caught between the French New Wave and the more traditional studio films of the time (this movement of which Louis Malle was a major contributor would become known as New French Cinema). Also included is a gallery and trailer as well as a very informative printed booklet including essays by Ben Sachs and Mani Sharpe as well as an excerpt from a speech given by cinematographer Pierre Lhomme during a Lifetime Achievement ceremony where he discusses his relationship with Cavalier. Sharpe’s essay is a bit more academic than Sachs but both are worth reading.

Le combat dans l’ile is a great film that is more deserving of a critical resurgence, and Cavalier is a director who is also deserving of recognition as more than a footnote, overshadowed by more well-known contemporaries.