Kôji Tsuruta is Gunji, a yakuza who has spent the last ten years in prison after partnering with the Daikato gang to take out a rival clan. Upon his return to Yokohama, he finds that the Daikato have basically taken over the town under the guise of going straight. Gunji decides to start over in the smaller, more isolated Okinawa but soon discovers that even that seemingly idyllic island has firmly entrenched obstacles on his road to takeover, including the Okinawa Yakuza and even the Daikato clan trying to muscle in on this turf. Get ready for an explosive climax of bloodshed and warring criminal enterprises seek to carve out a piece of Okinawa!

This early Kinji Fukasaku film feels very much in the spirit of his grand statement on the Yakuza gangster film, his Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, but on a smaller scale. Fukasawa has a knack for creating controlled chaos on film. The camera is restless, the music is jumping and the violence is explosive. Actors like Kôji Tsuruta and Noboru Andō seem almost tailor made for Fukasawa’s particular blend of tough guy fury. They exude a tough cool perfectly suited to the dangerous environment in which they find themselves. As Aaron Gerow points out in an extra on the disc, Okinawa traditionally has a reputation as a laid back place of comfort and relaxation, almost magical in how its twee depictions are often portrayed in media. But Fukasaku shows us the dark underbelly… The poverty and desperation inherently at the rotten core of an isolated location lacking major industrialization to bring forward thinking and progress to the region. It is actually quite easy to see small squabbles erupting into bloodbaths when cramming together such a volatile mix of people in such a constricted place. One element of the film deserving of being called out is the excellent jazzy, freewheeling score by Takeo Yamashita, an underrated composer who is perhaps most well-known for his work on the Lupin III anime series, but he also composed for several other Japanese gangster films and anime from this time period. His contributions are perhaps not as well-known because he seemed to drop out of the film industry in 1977, but that’s too bad. This film wouldn’t have the punch it has without the lively score orchestrating Fukasaku chaotic violence.

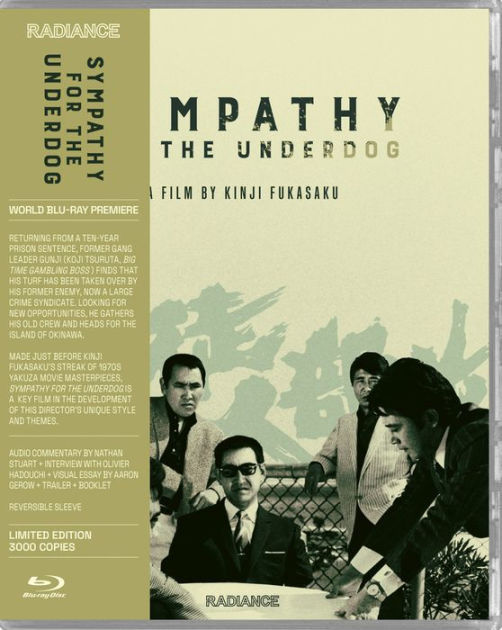

Radiance has once again delivered a nice, clean transfer for the most part. The digital transfer, provided directly to Radiance by Toei, is fairly grain-heavy but never too busy to become distorted. Fukasaku tends to employ intentionally gritty lo-fi handheld camerawork and this can be somewhat difficult to render sharply, particularly in low light. The dark scenes here look like they may have been artificially boosted a bit in order to avoid appearing overly murky, and I think generally it works. Overall, the film feels crisp and natural. The audio provided is a standard Japanese mono track and while a bit on the tinny side, sounds generally pretty clear. In particular, Yamashita’s score is represented well. For extras, Radiance has delivered another nice slate of meaningful additions to the disc. First we have an audio commentary from Japanese film expert Nathan Stuart and is a very informative commentary track on the film and the industry in Japan at the time. We also have an interview with Fukasaku biographer Olivier Hadouchi as well as the aforementioned visual essay on Okinawa by Aaron Gerow. Also included is a physical booklet contained a very good essay on the Japan film industry and Kinji Fukasaku’s place in it by festival programmer and film book author Bastian Meiresonne as well as a review of Sympathy for the Underdog taken from an issue of Kinema Junpo in 1971 by Tetsuo Iijima.

Sympathy for the Underdog is classic Fukasaku, charged with chaotic violence and a restless aesthetic to match. Fusing visuals, music, writing and acting into a heady brew that explodes like a powder keg, Fukasaku has given us a template for future successes, and Radiance has given us a great release in which to watch it.